This blog is a summary of an absolutely excellent 25 page article in JPEL Occasional Papers 48 2021 Issue 13 by Nicholas Boys Smith. Read it if you can, as it deserves a wider audience. While a lot of what is written is intuitive; very importantly it takes a number of qualitative issues, such as green is good for you and then sets out the results of empirical studies that confirm these hypotheses in a quantitative way.

The paper has 4 key points: good design is not subjective; the housing market is over concentrated with insufficient self and community build; use design codes; and, re-use older places and buildings.

To give two examples on good design:

Street trees are as close to a “no-regrets’ move as you will get. I have been forced to take out street trees on major planning applications, as the highway authority objected on safety and maintenance grounds. The key determinant of how fast we drive: is how safe the driver feels. Studies show that speeds are typically reduced by c. 7% where such trees are present and vehicle crashes reduced by between 5 and 20%. Moreover they improve air quality and moderate heat. Studies show people are also healthier in such environments and even drug prescriptions are reduced.

Facades Matter. Active frontages strengthen social ties, increase natural surveillance, improve sociability and increase the propensity to walk and therefore take exercise. Mixed–use land uses in one study showed that those people living in such areas used non motorised modes 12.2% of the time compared with 3.9% in single use communities. Modest semi public front gardens encourage neighbourliness. For example, one Danish study showed that in two parallel streets one with and one without front gardens 21 times more activity took place in those streets with front gardens.

The article goes on to really lambast the British planning approval system in lacking certainty, so the risks for developers up front are massive and costly. This has affected house prices, but also pushes the small builder and self-builder out of the market. Small builders only build 12% of our stock now (lower than anywhere else in Europe), yet even 30 years ago it was 40% in Britain. This lack of choice leads to too many poor homes and not enough of them.

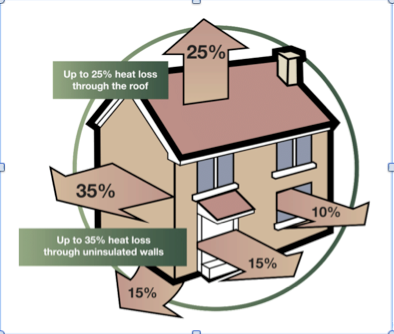

The article goes on to review sustainability and the green agenda. The thermal efficiency of new buildings and the location of (and transport to) places has been our focus. But there are three other factors which will influence the lifelong carbon footprint of new places and so far have been insufficiently considered: the form, shape and height of buildings; longevity (resilience and flexibility of design); and, the energy required for some materials.

So for example carbon emissions more than doubled going from 'low rise' to 'high rise’. The largest producer of waste in the U.K. is demolition and construction (24%). A new build two-bedroom house uses the equivalent of 80 tonnes of CO2; refurbishment uses 8 tonnes. Adaptability and flexibility is critically important. Materials also matter. Buildings using stone brick and wood, but not cement, fibre glass or aluminium have much lower embodied carbon.

In other words we have a long way to go in providing quality housing in beautiful, neighbourly and life enhancing places. And also a long way to go in planning buildings that least compromise our planet.